| Part of a series on | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hadith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

- Jan 21, 2019 AL-HUBB AL-NAAT IS A LARGEST COLLECTION OF NAATS-----AL HUBB AL NAAT is a islamic channel, in this channel we upload Naats in Many Languages. So You Can Listen urdu naat, punjabi naat, hindi.

- Sheikh al-Kulayni was succeeded by Sheikh as-Saduq as the leader of the Shia community. EDITOR’S NOTE: These articles are adaptations of lectures delivered by Maulana Sadiq Hasan in Karachi, Pakistan, during the 1980s on the lives of the great scholars of Islam. The Urdu lectures can be accessed at Hussainiat.com.

Al-Kafi is not a book independent of the Holy Quran. This volume simply provides beautiful details of the above matters as they are mentioned in various passages and verses of the Holy Quran. Oneness of Allah Part three of al-Kafi, volume one contains elaborate details of chapter 112 of the Holy Quran and other such passages therein.

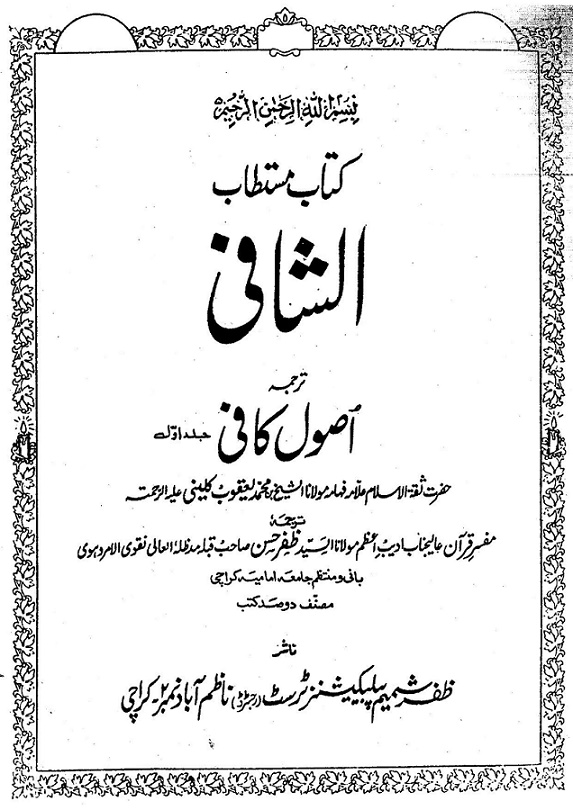

The book Al-Kāfī (The Sufficient Book) is a Twelver Shīʿīḥadīth collection compiled by Muhammad ibn Ya‘qūb al-Kulaynī.[1] It is divided into three sections: Usūl al-Kāfī, which is concerned with epistemology, theology, history, ethics, supplication, and the Qurʾān, Furūʿ al-Kāfī, which is concerned with practical and legal issues, and Rawdat (or Rauda) al-Kāfī, which includes miscellaneous traditions, many of which are lengthy letters and speeches transmitted from the Imāms.[2]In total, al-Kāfī comprises 16,199 narrations.[3]

Usūl(Fundamentals) al-Kāfī[edit]

The first eight books of al-Kāfī are commonly referred to as Uṣūl al-kāfī. The first type-set edition of the al-Kāfī, which was published in eight volumes, placed Usūl al-kāfī in the first two volumes. Generally speaking, Usūl al-kāfī contains traditions that deal with epistemology, theology, history, ethics, supplication, and the Qurʾān.

| Chapters | Traditions | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Kitāb al-‘aql wa al-jahl | The Book of Intellect and Foolishness | 36 traditions |

| Kitāb fadl al-‘ilm | The Book of Knowledge and its Merits | 176 traditions |

| Kitāb al-tawhīd | The Book of God and his Oneness | 212 traditions |

| Kitāb al-hujjah | The Book of Divine Guidance | 1015 traditions |

| Kitāb al-īmān wa al-kufr | The Book of Belief and Unbelief | 1609 traditions |

| Kitāb al-du‘ā' | The Book of Supplication | 409 traditions |

| Kitāb ‘adhamat al-Qur'an | The Book of the Qurʾān and its Merits | 124 Traditions |

| Kitāb al-muʿāsharah) | The Book of Social Intercourse | 464 traditions |

Furū al-Kāfī[edit]

Furū al-Kāfī: Books 9 through 34 are referred to as Furūʿ al-kāfī and are found in volumes three through seven of the first type-set edition. Furūʿ al-kāfī contains traditions that deal predominantly with practical and legal issues.

| Chapters |

|---|

| The Book of Purity |

| The Book of Menstruation |

| The Book of Funeral Rites |

| The Book of Prayer |

| The Book of Charity |

| The Book of Fasting |

| The Book of Ḥajj |

| The Book of Jihād |

| The Book of Commerce |

| The Book of Marriage |

| The Book of Animal Sacrifice upon the Birth of a Child |

| The Book of Divorce |

| The Book of Emancipation |

| The Book of Hunting |

| The Book of Slaughtering |

| The Book of Food |

| The Book of Drink |

| The Book of Clothing, Beautification, and Honor |

| The Book of Domesticated Animals |

| The Book of Testaments |

| The Book of Inheritance |

| The Book of Capital and Corporal Punishments |

| The Book of Restitution and Blood Money |

| The Book of Testimonies and Depositions |

| The Book of Adjudication and Legal Precedents |

| The Book of Oaths, Vows, and Penances |

Rawdat al-Kāfī[edit]

Rawdat al-Kāfī: The final book stands alone as Rawḍah al-kāfī, which is found in volume eight. Rawḍah al-kāfī contains nearly 600 miscellaneous traditions, many of which are lengthy letters and speeches, not arranged in any particular order.

| Title |

|---|

| The Book of Miscellanea -literally a garden from which one can pick many kinds of flowers |

Authenticity[edit]

Most Shia scholars do not make any assumptions about the authenticity of a hadith book. Most believe that there are no 'sahih' hadith books that are completely reliable. Hadith books are compiled by fallible people, and thus realistically, they inevitably have a mixture of strong and weak hadiths. Kulayni himself stated in his preface that he only collected hadiths he thought were important and sufficient for Muslims to know, and he left the verification of these hadiths up to later scholars.[citation needed] Kulayni also states, in reference to hadiths:

'whatever (hadith) agrees with the Book of God (the Qur'an), accept it. And whatever contradicts it, reject it'[citation needed]

According to the great Imami scholar Zayn al-Din al-`Amili, known as al-Shahid al-Thani (911-966/1505-1559), who examined the asnad or the chains of transmission of al-Kafi's traditions, 5,072 are considered sahīh (sound); 144 are regarded as hasan (good), second category; 1,118 are held to be muwaththaq (trustworthy), third category; 302 are adjudged to be qawī‘ (strong) and 9,485 traditions which are categorized as da'if (weak).[5]

Scholarly remarks[edit]

- The author (Muhammad ibn Ya'qub al-Kulayni) stated in his Preface of Al-Kafi:

'You said that you would love to have a sufficient book (kitābun kāfin) containing enough of all the religious sciences to suffice the student; to serve as a reference for the disciple; from which those who seek knowledge of the religion and want to act on it can draw authentic traditions from the Truthful [imams]—may God’s peace be upon them—and a living example upon which to act, by which our duty to God—almighty is he and sublime—and to the commands of his Prophet—may God’s mercy be on him and his progeny—is fulfilled...God—to whom belongs all praise—has facilitated the compilation of what you requested. I hope it is as you desired.'[6]

- Imam Khomeini (a prominent 20th century Shī‘ah scholar) said:

'Do you think it is enough [kafi] for our religious life to have its laws summed up in al-Kāfī and then placed upon a shelf?'[7]

The general idea behind this metaphor is that Khomeini objected to the laziness of many ignorant people of his day who simply kept al-Kafi on their shelf, and ignored or violated it in their daily lives, assuming that they would somehow be saved from Hell just by possessing the book. Khomeini argued that Islamic law should be an integral part of everyday life for the believer, not just a stale manuscript to be placed on a shelf and forgotten. The irony of the allusion is telling; Khomeini implicitly says that al-Kafi (the sufficient) is not kafi (enough) to make you a faithful Muslim or be counted among the righteous, unless you use the wisdom contained within it and act on * The famous Shī‘ah scholar Shaykh Sadūq didn't believe in the complete authenticity of al-Kāfī. Khoei points this out in his 'Mu‘jam Rijāl al-Hadīth', or 'Collection of Men of Narrations', in which he states:

أنّ الشيخ الصدوق : قدّس سرّه : لم يكن يعتقد صحّة جميع مافي الكافي

- 'Shaykh as-Sadūq did not regard all of the traditions in al-Kāfī to be Sahih (truthful).'[8]

The scholars have made these remarks, to remind the people that one cannot simply pick the book up, and take whatever they like from it as truthful. Rather, an exhaustive process of authentication must be applied, which leaves the understanding of the book in the hands of the learned. From the Shia point of view, any book other than the Qur'an, as well as individual hadiths or hadith narrators can be objectively questioned and scrutinized as to their reliability, and none - not even the Sahaba - are exempt from this.

The main criticism of al-Kafi as the basis for Shia fiqh, comes from prominent Sunni writers who argue that finding some hadiths in al-Kafi proves that the entire Shi'ite school is wrong. Shi'ites in reality do not rest the basis of their entire faith on the complete authenticity of this book ('Al Kafi' means 'the sufficient'). They believe that anything that goes against previously held ideas must not be authentic. They also do not automatically accept some hadiths from al-Kafi that have strong historical proofs.

The Qur'an is far more important to Islamic belief than any hadith book, and Shia scholars have long pointed this out.

Shia view of al-Kafi relative to other hadith books[edit]

Kulayni himself stated in his preface that he only collected hadiths he thought were important and sufficient for Muslims to know (at a time when many Muslims were illiterate and ignorant of the true beliefs of Islam, and heretical Sufi and gnostic sects were gaining popularity), and he left the verification of these hadiths up to later scholars. Kulayni also states, in reference to hadiths: 'whatever (hadith) agrees with the Book of God (the Qur'an), accept it. And whatever contradicts it, reject it'.[9]

The author of al-Kafi never intended for it to be politicized as 'infallible', he only compiled it to give sincere advice based on authentic Islamic law (regardless of the soundess of any one particular hadith), and to preserve rare hadiths and religious knowledge in an easily accessible collection for future generations to study.

Al-Kāfī is the most comprehensive collection of traditions from the formative period of Islamic scholarship. It has been held in the highest esteem by generation after generation of Muslim scholars. Shaykh al-Mufīd (d.1022 CE) extolled it as “one of the greatest and most beneficial of Shīʿah books.” Al-Shahid al-Awwal (d.1385 CE) and al-Muḥaqqiq al-Karakī (d.1533 CE) have said, “No book has served the Shīʿah as it has.” The father of ʿAllāmah al-Majlisī said, “Nothing like it has been written for Islām.”

See also[edit]

- Sharh Usul al-Kafi, a commentary on the Usul al-Kafi

- Branches of Religion (Furu al-din)

References[edit]

- ^Meri, Josef W. (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. USA: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-96690-0.

- ^Howard, I. K. A. (1976), ''Al-Kafi' by Al-Kulayni', Al-Serat: A Journal of Islamic Studies, 2 (1)

- ^http://www.al-islam.org/al-tawhid/kafi/1.htm Hadith al-Kafi

- ^Etan Kohlberg (1991). belief and law in imami shiism. Variorum. p. 523.

- ^'Selections from Al-Kulayni's Al-Kafi'.

- ^Islamic Texts Institute (2012). Al-Kafi Book I: Intellect and Foolishness. Taqwa Media. ISBN9781939420008.

- ^Wilayat al-Faqih: Al-Hukumah Al-Islamiyyah. p.72.

- ^(Arabic reference)

- ^http://www.answering-ansar.org/answers/umme_kulthum/en/chap7.php

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kitab al-Kafi. |

- 'Usul al-Kafi English Translation, E-Book Volumes 1-8', compiled by Muḥammad Ya`qûb Kulaynî, translated by Muḥammad Sarwar, published by the Islamic Seminary INC NY.

- 'Kiṫâbu-l-Kâfî', compiled by Muḥammad Ya`qûb Kulaynî, published by the Islamic Seminary INC NY, translated by Muḥammad Sarwar.

Al Kafi In Urdu

| The Fourteen Infallibles | |

|---|---|

| |

| Principles | |

| Other beliefs | |

| Practices | |

Others | |

| Holy cities | |

| Groups | |

| |

| Scholarship | |

| |

| Hadith collections | |

| Related topics | |

| Related portals |

|

Shahrbānū (or Shehr Bano) (Persian: شهربانو; 'Lady of the Land')[1] was allegedly one of the wives of Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and the third TwelverShiaImam, as well as the mother of his successor, Ali ibn Husayn.[2] She was reportedly a Sassanid princess, a daughter of Yazdegerd III, the last Sassanid emperor of Persia.[3] Shahrbanu has also been referred to with several other names by different writers, such as: Shaharbānawayh,[4]Shahzanān,[5]Shahjahan,[6]Jahanshah,[7]Salāma,[8]Salāfa,[9]Ghazāla,[10] and Sādira.[11]

Islamic legends state that Shahrbanu was captured during the Muslim conquest of Persia. When presented before the Arab nobility and offered a choice in husband, she requested to be given in marriage to Husayn.[1] The majority of Shia sources state that Shahrbanu subsequently died shortly after giving birth to her son Ali[12][13] and was buried in the Jannat al-Baqi, alongside other members of Muhammad's family. Some traditions however, indicate to the Bibi Shahr Banu Shrine in Rey being her resting place.[1]

Shahrbanu is viewed as a saintly figure by both the Shia and Sunni denominations and is especially revered in Iran, her importance being partly tied to the link she provides between pre-Islamic Persia and modern Shi'ism. However, her historicity is uncertain. Islamic writers, such as al-Mubarrad, Ya'qubi and al-Kulayni, began alluding to Shahrbanu and her imperial Persian background from the 9th century onward. However, the earliest sources make no mention of the mother of Ali ibn Husayn, nor do they ascribe him with maternal royal ancestry. The first references were from Ibn Sa'd and Ibn Qutaybah, also in the 9th century, who instead describe her as being a slave from Sindh. The Encyclopædia Iranica surmises that Shahrbanu was 'undeniably legendary'.[1]

Family background[edit]

Islamic histories regarding Shahrbanu generally state that she was a daughter of Yazdegerd III, the last Sassanid emperor of Persia.[3] However, other identifications for her parentage have also been given. Muhammad ibn Ahmad Naysaburi cites a tradition that she was the daughter of Yazdegerd's father, Prince Shahriyar, son of Khosrow II. Ibn Shahr Ashub relates that her father was the nushijan, a Persian ruler whose identity has not yet been further clarified. These are minority views however, with the belief of her being the daughter of Yazdegerd being the most prevalent.[14]

Accounts are silent regarding Shahrbanu's mother. Yazdegerd is recorded to have had several wives and concubines,[15] with Al-Tabari and Ibn Khaldun making specific references to a marriage he had made to a woman in Merv.[16][17] However, Zameer Naqvi believes Shahrbanu's mother to have been a Sindhi princess named Mah Talat or Maha Talat. She may have been a member of the Buddhist Rai dynasty, with who the Sassanid emperors had maintained good relations. The present city of Matli, where her marriage to Yazdegerd supposedly took place, may have been named after her.[18][19]

In addition to Shahrbanu, the historian Al-Masudi provides the names of four other children of Yazdegerd III; two sons, namely Peroz and Bahram, and two daughters, Adrag and Mardawand.[20] While it was historically recorded that her brothers had escaped to the Tang emperor of China,[20] Islamic traditions state that Shahrbanu's sisters were captured alongside her. One allegedly married Abdullah, son of the Caliph Umar, and became the mother of his son Salim, while another married Muhammad, son of the Caliph Abu Bakr, and became the mother of his son Qasim.[21] Further alleged siblings have also been attributed to Shahrbanu, including Ghayanbanu, who was her full sister,[19] Izdundad, who married the Jewish exilarch Bostanai,[22] and Mihrbanu, who married Chandragupta, the Indian king of Ujjain.[23]

Capture and marriage[edit]

Accounts of Shahrbanu's capture generally state that she was taken during the Muslim conquest of Khorasan, either by Abdallah ibn Amir or Hurayth ibn Jabir.[24][14] The princess (possibly alongside her sisters)[21] was subsequently brought as a slave to Medina, where she was presented to the Caliph, who al-Kulayni identifies as being Umar ibn al-Khattab.[24] A hadith reported by as-Saffar al-Qummi in the Basa'ir ad-Darajat gives the following account of Shahrbanu's arrival at Umar's court:[7]

When they sought to take the daughter of Yazdegerd to Umar, she came to Medina; young girls climbed higher to see her and the Prophet's mosque was illuminated by her radiant face. Once she caught sight of Umar inside the mosque, she covered her face and sighed: 'Ah piruz badha hormoz' (Persian: May Hormuz be victorious). Umar became angry and said: 'She is insulting me.' At this point, the Commander of the Faithful (Ali ibn Abi Talib) intervened and said to Umar: 'Do not meddle, leave her alone! Let her choose a man among the Muslims and he will pay her price from the spoils he earned.' Umar then said to the girl: 'Choose!' She stepped forward and placed her hand on Husayn's head. The Commander of the Faithful asked her: 'What is your name?' 'Jahan Shah' she answered. And Ali added: 'Shahrbanu also.'[a] He then turned to Husayn and said to him: 'Husayn! She will be the mother of your son who shall be the best of those living in the world.'

Shia Book Al Kafi In Urdu Pdf

There is disagreement between various accounts regarding the details of the story. In al-Kulayni's Kitab al-Kafi, it was Umar's decision for Shahrbanu to choose her own husband, as opposed to Ali's. Keikavus'Qabusnama includes the involvement of Salman the Persian.[26] The Uyun Akhbar al-Ridha by Ibn Babawayh reports that the caliph in question was not actually Umar, but his successor, Uthman. In relation to this, historian Mary Boyce states that al-Qummi's account ignores that the conquest of Khorasan took place during the latter's reign, as well as the fact that Shahrbanu's supposed son, Ali, was not born until over a decade after Umar's death.[24]

Death[edit]

The earliest sources regarding Sharbanu make no mention of her ultimate fate, instead primarily focusing on the events of her capture and marriage.[24] Later accounts added further details to the story, with multiple variations emerging regarding her death. Literary traditions state that she died upon giving birth to her son, Ali ibn Husayn in 659 CE.[1] She was allegedly buried in the Jannat al-Baqī in Medina, her grave being beside that of her brother-in-law Hasan ibn Ali.[24]

Another account narrates that Shahrbanu lived to see the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE. Having witnessed the massacre of her family during the battle, the princess drowned herself in the Euphrates to avoid the humiliation of captivity by the Umayyads.[27]

A third version, as with the previous account, states that Shahbanu was alive during Karbala, but includes a miraculous aspect to the story. It states that prior to his death, Husayn gave Shahrbanu his horse and bid her to escape back to her homeland in Persia. She was closely pursued by Yazid's soldiers and as she approached the mountains surrounding Rey, she tried to call out for Allah in desperation. However, in her exhaustion she misspoke and rather than saying 'Yallahu!' (Oh Allah!), she said 'Ya kuh!' (Oh mountain!). The mountain then miraculously opened and she rode into it, leaving behind only a piece of her veil which had gotten caught as the chasm closed behind her. This became an object of veneration, with the area becoming a shrine as well as a popular pilgrimage site.[28][1]

Mary Boyce believed that the latter story was a 10th century invention, considering it to be probable that the shrine was previously dedicated to the Zoroastrian goddess Anahid. She states that as Zoroastrianism and the worship of Anahid became less predominant in the region, a link was probably formed between the site and Shahrbanu in order for the veneration of the Persian princess to take its place. It is also notable that the word 'Banu' (Lady) is strongly associated with Anahid, making it likely that 'Shahrbanu' (Lady of the land) was the title originally used to dedicate the old shrine.[29]

Historicity[edit]

The historicity of Shahrbanu is highly debatable, with no source that can truly confirm or deny her existence.[30] While it was certainly within the influence of Husayn's father, Ali ibn Abi Talib, to have had him married to a captive daughter of Yazdegerd III,[31] contemporary sources make no mention of such an event. Early histories regarding the invasion of Persia by authors such as Ibn Abd Rabbih and al-Tabari, often written with great attention to detail, do not establish any relationship between the Sassanid royal family and a wife of Husayn. The same is true for a wide range of sources, such as the Hanafi judge Abu Yusuf in his treatise on taxation, the Kitab al-Kharaj, nor Ferdowsi in his epic, the Shahnameh.[1]

The first mentions of the mother of Ali ibn Husayn come two hundred years later from Ibn Sa'd and Ibn Qutaybah in the 9th century, who both describe her as a slave from Sindh named Gazala or Solafa. They go on to claim that after the death of his father, Ali freed his mother and gave her in marriage to a client of Husayn's named Zuyaid, to whom she bore a son, Abdullah.[1][32]Ya'qubi, who wrote around the same time as Ibn Qutaybah, was the first to suggest that Ali's mother was an enslaved daughter of Yazdegerd, stating that she was nicknamed Gazala by Husayn. The Tarikh-i Qum and the Firaq al-Shi'a, both written around the 10th century, give a similar story, but state that she was originally called either Shahrbanu or Jahanshah and was later renamed Solafa.[33]

There is therefore a consistency between the early sources that the mother of Ali was named Gazala or Solafa, and that she was an eastern slave belonging to Husayn. The dispute only arises regarding her original identity and subsequent fate. Ibn Babawayh however, also writing in the 10th century, records a Shia tradition that combines the two stories. It states that Ali was the son of a daughter of Yazdegerd who died in childbirth. He was subsequently raised by a concubine of Husayn's, who was publicly assumed to be his mother. When Ali later arranged for the concubine to be married, he was mocked due to the belief that he had given his own mother away. This tradition acts to support the earlier accounts whilst also providing an explanation for the contradictions. Based on the various testimonies, Mary Boyce surmised that Ali's mother was a Sindhi concubine, who he later freed and arranged to be married. The Shahrbanu story subsequently emerged to explain away the aspects which may have been viewed as unpalatable.[24]

It is also thought that the legend of Shahrbanu was used to provide a link between pre-Islamic Persia and Shi'ism, something which is thought to be an extremely important aspect for the Persian converts of the period. Through Shahrbanu, the Shia Imams would have possessed legitimacy in two forms: through their paternal descent from Ali ibn Abi Talib and Fatima, daughter of Muhammad, and their maternal descent from the ancient Persian kings.[34] Later incarnations of the story may have magnified the Persian aspect with this in mind, with increasing emphasis put on the princess's royalty. Ali ibn Abi Talib plays an important role in this, with he and Shahrbanu conversing in Persian, him insisting on her freedom and nobility of rank as well as predicting the birth of the future Imam.[1] It is also notable that for several centuries, the writers who reported the story had almost exclusively been Persians or Persianized Shias, such as al-Kulayni, Ibn Babawayh and Ibn Shahr Ashub.[35] Subsequently, it appears that Shahrbanu served as a factor in the convergence between the persecuted Shias and the conquered Persians.[34] A similar effort was attempted several centuries later to connect the mother of the twelfth Imam to the Byzantine emperors and the Apostle Simon, thereby linking the Imams to Shi'ism, Mandaeism, and Christianity, though this proved less successful.[35]

Iranian scholar and politician Morteza Motahhari argued against this reasoning, stating that the Shia Imams' potential Sassanid ancestry would not have especially attracted Persians to Shi'ism. Noting that the mother of the Yazid III is believed to be a daughter of Peroz III,[36] Motahhari added that the Persians had no equivalent inclination towards the Umayyad dynasty. Similarly, the Umayyad general Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad is also not especially esteemed based on his maternal Persian heritage. In addition to this, Motahhari asserted that Shahrbanu is not venerated in Iran above the mothers of the other Imams, who came from a multitude of ethnic backgrounds, such as Narjis, who is believed to have been a Roman concubine.[37]

Notes[edit]

- ^It is uncertain whether Ali was merely mentioning another name that the princess was known by, or if he was conferring upon her an entirely new name.[25]

References[edit]

- ^ abcdefghiAmir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (July 20, 2005). 'ŠAHRBĀNU'. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^Michael Curtis, Religion and Politics in the Middle East (1982), p. 132

- ^ abMehrdad Kia, The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol. I (2016), p. 6

- ^(1)Roudat al-Wa'zin, vol. 1, p. 237. (2) 'Uyyun al-Mu'jizat, p. 31.(3) Ghayat al-Ikhtisar, p. 155.

- ^Al-Shiblanji, Nur al-Abbsar, p. 126.

- ^Boyce, Mary (December 15, 1989). 'BĪBĪ ŠAHRBĀNŪ'. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- ^ abAmir- Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (31 January 2011). 'The Spirituality of Shi'i Islam: Beliefs and Practices'. I.B.Tauris. p. 50. Retrieved 23 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^(1) 'Usul al-Kafi, vol. 1, p. 466. (2) Siyar 'Alam al-Nubala', vol, 14, p. 237 (3) Kalifa Khayyat, al-Tabaqat, p. 238.(4) Al-Nisaburi, al-Asami wa al-Kuna.

- ^(1) Al-Dhahabi, Tarikh al-Islam, vol. 2, p. 46.(2)Al-Imama fi al-Islam, p. 116. (3) Ansab al-Ashraf, p. 102. (4) AlBustani, Da'irat al-Ma'arif, vol. 9, p. 355.(5) Nur al-Abbsar, p. 136. (6) Al-Kamil, vol. 2, p. 464.

- ^(1)Safwat al-Safwa, vol. 2, p. 25. (2) Shadharat al-Dhahab, vol. 1, p. 104.(3) Sir al-Si;sila al-'Alawiya, p. 31. (4) Nihayat al-Irab, vol. 21 p. 324. (5) Kulasat al-Dhahab al-Masbuk, p. 8.

- ^Al-Ithaf bi Hub al-Ashraf, p. 49.

- ^(1) Al-Mas'udi, Ithabat al-Wasiya, p. 143. Imam Zayn 'al-Abidin, p. 18

- ^Baqir Sharif al-Qarashi. The life of Imam Zayn al-Abideen a.s. p20-21

- ^ abMoshe Gil, The Babylonian encounter and the Exilarchic House in the light of Cairo Geniza documents and parallel Arab sources, Judaeo Arabic Studies, (2013), p. 162 [1]

- ^Irving, Washington. Mahomet and His Successors (1872 ed.). Philadelphia,. p. 279.

- ^Habib-ur-Rehman Siddiqui (Devband), Syed Muhammad Ibrahim Nadvi. Tareekh-e-Tabri by Nafees Academy (in Urdu). Karachi Pakistan. pp. 331–332 Vol-III.

- ^Illabadi, Hakeem Ahmed Hussain. Tareekh-e-Ibn Khaldun by Nafees Academy (in Urdu) (2003 ed.). Karachi Pakistan. p. 337.

- ^Syed Zameer Akhtar Naqvi, Allama Dr. (2010). Princess of Persia – Hazrat Shahar Bano (in Urdu). Karachi, Pakistan: Markz-e-Uloom-e-Islamia (Center for Islamic Studies). p. 290 (Chapter-VIII).

- ^ abAfsar, Mirza Imam Ali Baig. Sindh and Ahle Bayt (in Urdu). Tando Agha Hyderabad, Sindh, Pakistan: Mohsin Mirza Publication. pp. 34–36.

- ^ abMatteo Compareti (July 20, 2009). 'Chinese-Iranian Relations xv the Last Sassanians in China'. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ abShaykh Muhammad Mahdi Shams al-Din, The Authenticity of Shi'ism, Shi'ite Heritage: Essays on Classical and Modern Traditions (2001), p. 49 [2]

- ^Peter Crawford, The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam (2013), p. 207 [3]

- ^Carla Bellamy, The Powerful Ephemeral: Everyday Healing in an Ambiguously Islamic Place (2011), p. 209 [4]

- ^ abcdefMary Boyce, Bībī Shahrbānū and the Lady of Pār, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 30, No. 1, Fiftieth Anniversary Volume, (1967), p. 34-5

- ^Amir-Moezzi (2011, p. 52)

- ^Boyce (1967, p. 61)

- ^Amir-Moezzi (2011, p. 62)

- ^Boyce (1967, p. 33)

- ^Boyce (1967, p. 35-8)

- ^D. Pinault, Horse of Karbala: Muslim Devotional Life in India (2016), p. 71

- ^Salo Wittmayer Baron, A Social and Religious History of the Jews - Volume 1 (1957), p. 270

- ^Boyce (1967, p. 33-4)

- ^Boyce (1967, p. 34)

- ^ abMohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, Christian Jambet, What is Shi'i Islam?: An Introduction (2018), ch. 2

- ^ abAmir-Moezzi (2011, p. 99-100)

- ^Patricia Crone, The Nativist Prophets of Early Islamic Iran: Rural Revolt and Local Zoroastrianism (2012), p. 5

- ^Ayatullah Murtada Mutahhari (Translated from the Persian by Dr. Wahid Akhtar) (1989). 'Islam and Iran: A Historical Study of Mutual Services – Part 2'. Al-Tawhid (A Journal of Islamic Thought and Culture ). Retrieved July 2, 2016.

Further reading[edit]

- S.H. Nasr and Tabatabaei. Shi'a Islam. 1979. SUNY Press. ISBN0-87395-390-8

- Safavī, Rahīmzādah. Dāstān-i Shahrbānū. 1948. LCCN76-244526

- Sayyid Āghā Mahdī Lakhnavī, Savānih Hayāt-i Hazrat Shahr Bāno. LCCN81-930254. Reprint 1981.

- 'Aldarajat ol Rafi' (الدرجات الرفیع) p215.

- 'Mu'jem ol Baladan' (معجم البلدان) Vol 2 p196.

- 'Nahj al Balagha' letter 45.

- 'Nahj al Balagha' Sobhi Saleh sermon 209 (خطبه صبح صالح).

- 'Nafs al-Rahman' (نفس الرحمان) p139.

- 'Managhib ebne shahr ashub' (مناقب ابن شهر اشوب) Vol 4, p48.

- 'Iranian dar Qoran va revayat.' Seyed Noureddin Abtahi (ايرانيان در قرآن و روايات / نور الدين ابطحى). Chapter 3. ISBN964-6760-40-6. LCCN2005-305310